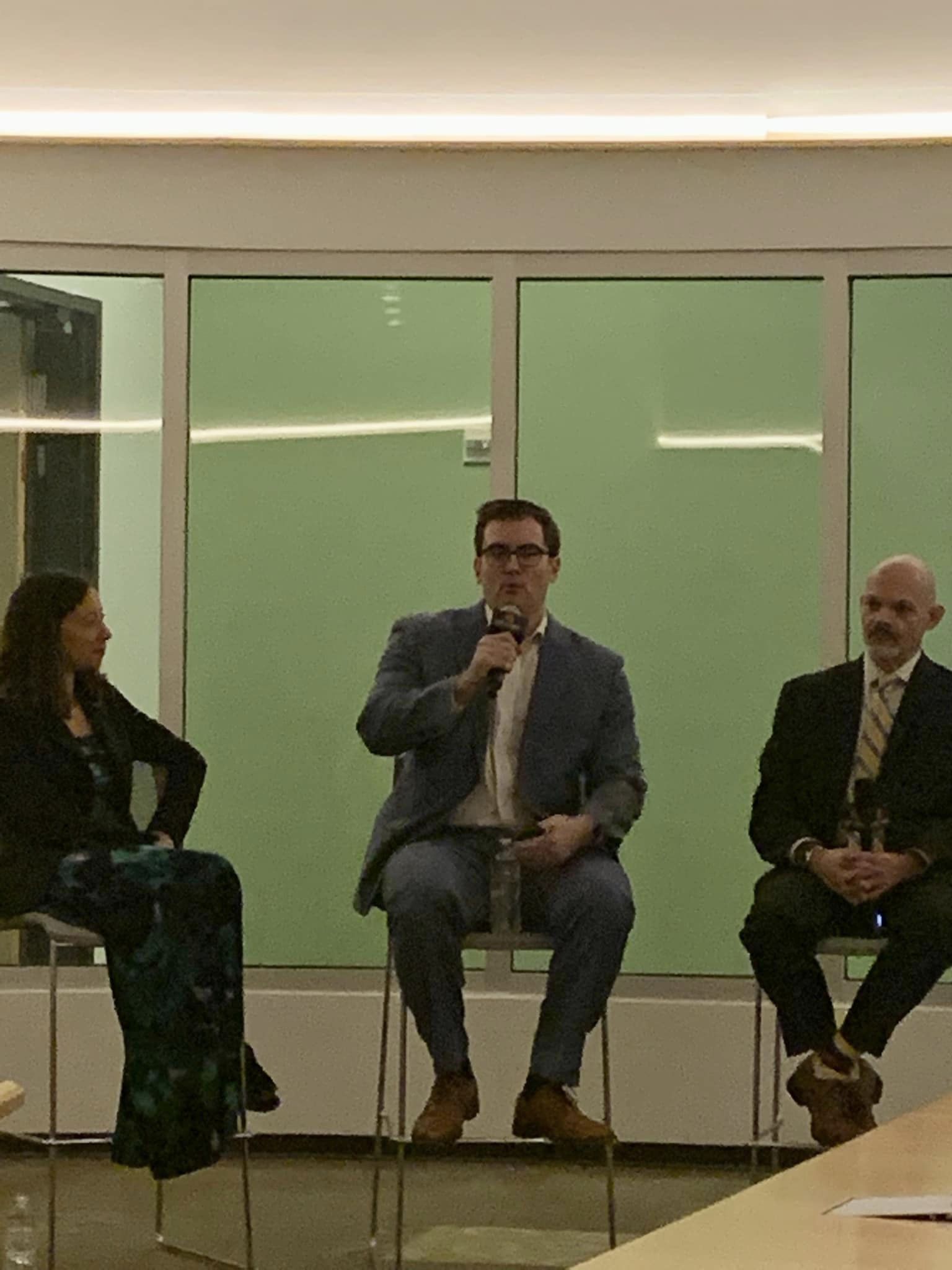

Eric Rubenstein and I shared our thoughts on a panel last week moderated by Hema Saxena (Schellman) and were joined by other experts: Ian Johnson (Losey PLLC); Richard Ryan, CDPSE, CGEIT, CIPP/US, CISA, CISSP, PCIP (Conduent); and Mesha S. The hybrid panel had a physical footprint at Full Sail and the topic was safeguarding personal privacy online.

Although our focus is typically HITRUST and B2B IT security controls, we shared some information for small business owners and people of the community about protecting their personal information (PII) beyond their health information (PHI).

Everyone leaves a digital footprint whenever they use the internet, from the most basic to most sensitive, with the constant share of data, our privacy has become thinner and risks of breaches increase. Hema shared that “67% of internet users in the US are not aware of their country’s privacy.” Basic ways to protect online privacy were shared from strong passwords to opening untrusted links and oversharing on social media. The concept, however, of tightened privacy impeding innovation is one that had to be discussed. Typically the US has been more lax about privacy laws due to innovation, so the question becomes what is the best way to enforce data privacy while not impeding future innovation? The panel suggested it was a matter of being smart and only providing data necessary and nothing extra. Everyone does not need to know your birthday from Facebook.

The “pay yourself” scam and protecting yourself is a good example of how to be more vigilant as phishing schemes become better. First the victim will receive a text message that looks like a fraud alert from their bank. It may reference unusual activity like “Did you make a purchase of $50.00 at XYZ Merchant?” and XYZ Merchant could be Amazon or something common to the victim.

If the victim responds to the text, they have then engaged the scammer and a call from what looks to be the bank will come in. The call is made by someone who appears to be a representative from the bank and will offer to help stop the fraud by asking the victim to send money to themselves with Zelle®. The scammer will ask for the one-time code the victim just received from the bank and if the victim gives the code, it will be used to enroll their bank account with Zelle® using phone number or email.

This simple small action gives the scammer the ability to receive the victim’s money into their own account. If you would like to go home and tell your parents and children to protect themselves, share that they should not always trust caller ID – although it looks like the bank, it might not be. Also, they should not share codes based on a call received and never be pressured to act immediately.

Recent Comments